Is Chemotherapy Ever Covered Under Federal Emergency Services

Share

Medicaid: Ensuring Access to Affordable Health Care Coverage for Lower Income Cancer Patients and Survivors

Introduction

Medicaid plays a vital role in providing affordable health care coverage to lower income cancer patients and survivors. Following enactment of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), expansion of state Medicaid programs ensured that more cancer patients and survivors would have access to critical treatment and survivorship care. More than two million Americans (children and adults under age 65) with a history of cancer rely on Medicaid for their health care.1

The structure of Medicaid and the flexibility states have to alter their programs, through the Section 1115 Research and Demonstration Waiver process (under the Social Security Act), provide unique opportunities for states to try novel approaches to care through the use of demonstration waivers. Unfortunately, a number of the waivers being proposed by states also have the potential to limit care.

In order to fully understand the importance of Medicaid to cancer patients and survivors, this paper provides an overview of the basic structure of the program – who is eligible, the available benefits and how Medicaid is financed. It also examines the potential impact of the policy proposals currently under discussion at both the state and federal levels on cancer patients, survivors and those at risk for cancer.

The Nuts and Bolts of Medicaid

Eligibility

Medicaid is a health care program administered by each state under broad federal guidelines. It provides comprehensive and affordable health coverage to nearly 65 million low- and modest-income Americans.2, 3 The costs of the program are shared by state and federal governments.

When it was first established in 1965, Medicaid was available primarily to mothers and their children who were enrolled in the Aid for Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program;4 and blind, disabled, and elderly individuals eligible for the Supplemental Security Income program. For individuals to qualify for each of those programs, family income needed to be very low, in most states a fraction of the federal poverty level (FPL).

Beginning in the 1980s, Congress created new coverage pathways to Medicaid for low-income individuals and families. Some of the new coverage groups were mandatory for state Medicaid programs; others were optional for states. The coverage expansions initially focused on pregnant women and infants in families, later expanding to cover low-and modest-income children;5 working families; additional low-income elderly individuals; disabled individuals with jobs; and people in need of long-term care services and supports.

An important pathway to Medicaid was enacted in 2000 permitting states to cover certain uninsured and underinsured women under age 65 who are in need of treatment for breast or cervical cancer, including for pre- cancerous conditions.6 Women qualifying for Medicaid eligibility under this pathway must be identified through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) and have income below 250% FPL. States providing women access to Medicaid through the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment option received enhanced federal funding toward the cost of Medicaid for those women. All 50 states, the District of Columbia, 6 U.S. territories, and 13 American Indian/Alaska Native tribes or tribal organizations presently offer that coverage, though income levels and coverage vary by state.7, 8

Before 2010 however, coverage for low-income adults who were neither pregnant nor caring for dependent children was extremely limited. Even for parents, most states severely limited eligibility for Medicaid. When those groups were covered, such coverage was generally offered under an 1115 waiver as there were no pathways to eligibility and coverage in the traditional Medicaid program.

In 2010, the ACA ushered in a major Medicaid coverage expansion. As enacted, the law would have required states to extend Medicaid coverage to all adults with incomes below 138% FPL.9 That expansion would have transformed the Medicaid program by establishing a federal benchmark through which all individuals with incomes below 138% FPL ($17,236/year or $1,436/month for a single adult in 2019), nationwide, would qualify for Medicaid whether or not they were in a family with dependent children or had any particular health condition or disability. For the first time, nationwide coverage would be provided for all low-income adults including those with cancer and survivors.

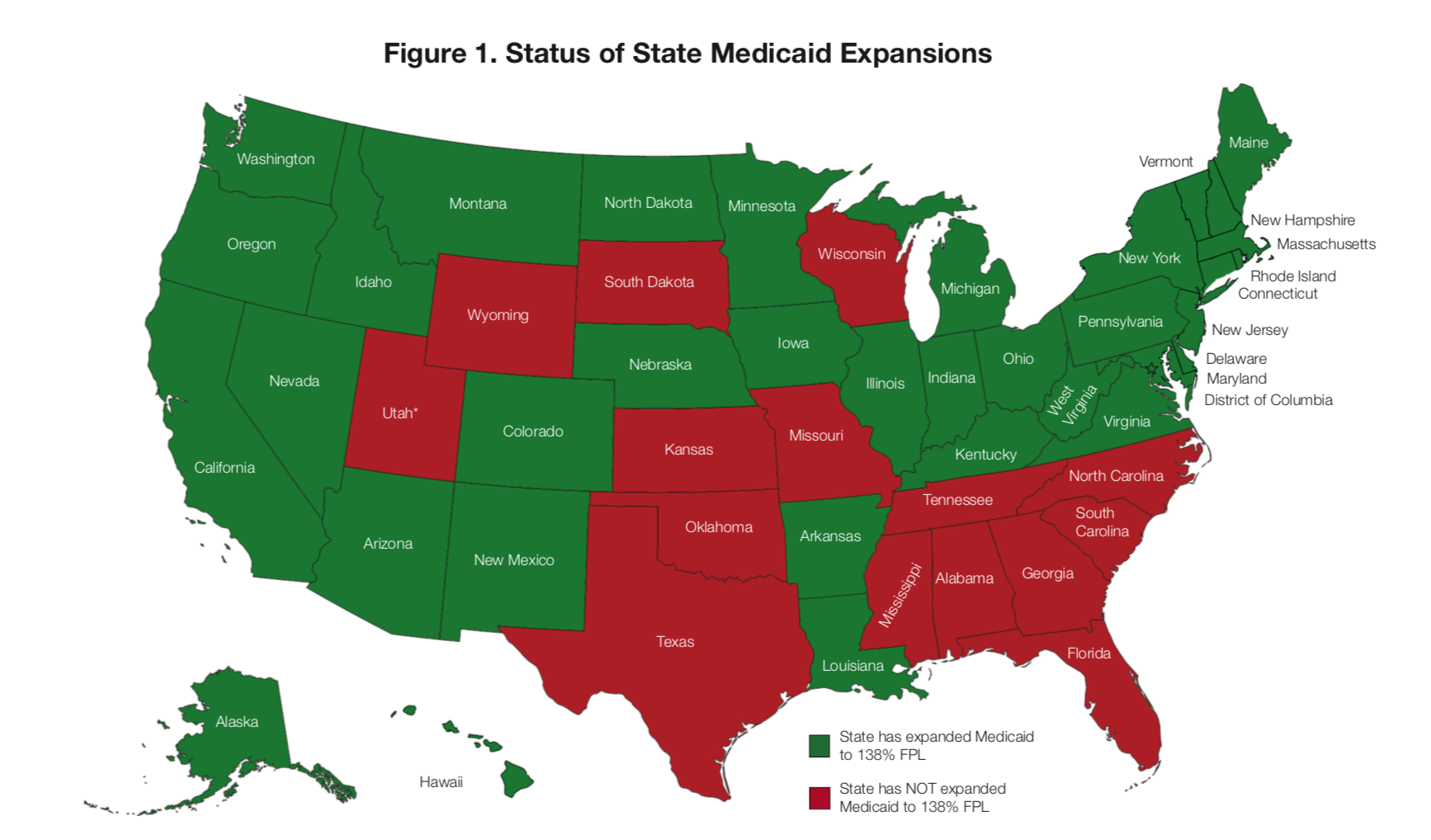

However, the coverage expansion was never implemented nationwide. Instead, the Supreme Court decided in King v. Burwell10 that the ACA's Medicaid expansion must be interpreted as optional for states. Since that decision, as of December 1, 2019, 35 states plus the District of Columbia have chosen to expand Medicaid coverage for adults with income below 138% FPL. (see Figure 1.) In the remaining states, most low-income adults and parents do not qualify for Medicaid (although several states are considering action that could result in future Medicaid expansions for adults eligible under the ACA).11

Adults with income below the poverty level in non-expansion states are in what is referred to as the "coverage gap." They do not qualify for the traditional Medicaid program, because they earn too much to qualify and because their income is below the poverty level, and they also do not qualify to receive tax credits to help with the cost of private health insurance available through the ACA exchange or Marketplace. Tax credits or "subsidies" are only available to individuals with income at or above the FPL.

Notes: In 2018, Utah voters passed a ballot initiative to expand Medicaid up to 138% FPL. In the Spring of 2019, legislation was enacted, authorizing the state to apply for an 1115 waiver to provide limited coverage to adults, only up to 100% FPL. In July 2019, the partial expansion waiver was not approved by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). At the time of publication, the state of Utah drafted a subsequent waiver to fully expand up to 138% FPL.

Source: "How Do You Measure Up? A Progress Report on State Legislative Activity to Reduce Cancer Incidence and Mortality." American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, 2019. https://www.fightcancer.org/sites/default/files/National%20Documents/HDY....

Benefits

Medicaid provides many of the same benefits as private health insurance. Every state's Medicaid program is required to cover certain services including: inpatient and outpatient hospital services, physician services, tobacco cessation counseling for pregnant women, certain preventive services, and laboratory and x-ray services. States also have the option to cover additional benefits including: prescription drugs (currently all states cover prescription drugs), non-mandatory preventive care, dental services for adults, hospice, and physical therapy, among many others.12

As such, Medicaid coverage varies considerably between the 50 states and the District of Columbia. For example, while all states are required to cover inpatient hospital services, there are significant differences among states as to how many hospital days per episode or per year are covered. The result is that Medicaid benefits differ considerably from one state to the next.

Many governors and other lawmakers, however, continue to press for further program flexibility. Many indicate that with the federal requirements in place under existing law and regulations, they have very little control over program spending.13

Financing

States and the federal government share the cost of the Medicaid program. For most expenditures in the traditional Medicaid program, the federal share (federal matching assistance percentage or "FMAP") can be no lower than 50% in any state and, except in specific instances where the share is specified to be higher, it cannot exceed 83%. Medicaid's matching formula ensures that poorer states pay a smaller share of program costs and wealthier states pay half. On average across all states, the federal government pays about 62% of program costs with states paying the remaining 38%. For individuals eligible under Medicaid expansion, the federal share of costs is 93% and the state share is 7% of those costs in 2019 and drops down to 90% and 10%, respectively, in 2020 and beyond. According to federal law, the federal FMAP cannot drop below 90% for the expansion population.

The Impact of Medicaid & Medicaid Expansion on People with Cancer and Cancer Survivors

Medicaid is an important source of coverage for people with cancer and cancer survivors. More than two million Americans (children and adults under age 65) with a history of cancer rely on Medicaid for their health care, and in 2014 nearly one-in-three children diagnosed with cancer were enrolled in Medicaid at the time of their diagnosis.14

While a limited number of adults with cancer qualified for coverage through a traditional Medicaid eligibility category, Medicaid expansion has dramatically increased access to health coverage for parents and adults who need cancer care, have a history of cancer, as well as those who may face a cancer diagnosis that reside in an expansion state. While most expansion states provide all low-income parents and adults access to health insurance coverage through Medicaid, countless individuals living in non-expansion states continue to lack access to a comprehensive, affordable health insurance coverage option.

Reducing the Number of Uninsured

Almost every year since the 2010 passage of the ACA, access to Medicaid has increased even while the number of uninsured adults has begun to increase again.15 States that opted to expand Medicaid have experienced, and continue to experience, large reductions in the rates of uninsured when compared with states that didn't expand Medicaid. After two years, expansion states had uninsured rates 8.2% lower than non-expansion states.16 This impact has not only been maintained but has increased over time. Four years after expansion, uninsured rates of low-income adults in expansion states were estimated to be 12 percentage points lower than that in a comparable group in non-expansion states.17 A large and growing body of literature has come to similar conclusions.18

Medicaid expansion has proven to be a critical health insurance coverage option among people diagnosed with cancer and cancer survivors. The lack of insurance among those individuals has declined considerably. For example, the reduction in the percentage of uninsured people newly diagnosed with cancer was 1.3 percentage points greater in expansion states than non-expansion states.19 Cancer survivors experienced similar declines in rates of uninsurance. Comparing expansion states to non-expansion states, the share of cancer survivors without insurance declined from 12.4% to 7.7% taking into account both Medicaid and ACA individual market subsidies.20

Research shows that states opting to expand Medicaid under the ACA were successful in increasing access to care, improving self-reported health, and reducing mortality among adults:21

Medicaid Enrollees are More Likely to Have a Usual Source of Care. When compared to people without health insurance coverage, Medicaid enrollees have considerably better access to care across a number of measures. They are more likely to report having a usual source of care and visits with a general physician or with a specialist over the past year. Their reliance on the emergency department for treatment declines and they're less likely to delay seeking medical care.22 Compared to cancer survivors in non- expansion states, those in expansion states had a significantly higher likelihood of having a personal doctor and were less likely to be unable to see a doctor because of cost.23

- People with Medicaid are More Likely to Receive Preventive Care and Cancer Treatment Services.

The uninsured are more likely to forgo preventive care when compared to those with insurance coverage. They receive significantly less cancer care than people with insurance and have poorer health outcomes.24 One in five (20%) nonelderly adults without coverage say that they went without care in the past year because of cost compared to 3% of adults with private coverage and 8% of adults with public coverage (including Medicaid).25 When followed-up over time, the uninsured are more likely to report that they are no longer receiving cancer treatment.26

Medicaid expansion has been associated with increasing cancer screening rates across a number of different types of cancer screening. Screening rates for breast cancer, cervical cancer, and colorectal cancer have all been found to be higher or to have increased more in ACA expansion states when compared to the same rates in non-expansion states:

Table 1. Cancer Screening by Health Insurance Status in Adults

| Under 138% FPL in expansion states | Under 138% FPL in non-expansion states | |

| Mammogram in the past 2 years | 68.2 % | 62.7% |

| Pap Test in the past 3 years | 81.0% | 74.3% |

| Source: Sabik, Lindsay M., Wafa W. Tarazi, and Cathy J. Bradley. "State Medicaid Expansion Decisions and Disparities in Women's Cancer Screening." American Journal of Preventive Medicine 48, no. 1 (January 2015): 98–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.015. | ||

| Very early expanding states* | Non-expansion states | |

| Change in the percentage of people receiving colorectal cancer screening in the past 2 years | +8% | +2.8% |

| Source: Fedewa, Stacey A., K. Robin Yabroff, Robert A. Smith, Ann Goding Sauer, Xuesong Han, and Ahmedin Jemal. "Changes in Breast and Colorectal Cancer Screening After Medicaid Expansion Under the Affordable Care Act." American Journal of Preventive Medicine 57, no. 1 (July 2019): 3–12. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.02.015. | ||

| States that expanded Medicaid | Non-expansion states | |

| Colorectal cancer screening | 34.1% | 26.8% |

| Cervical cancer screening | 58.1% | 52.8% |

| Source: Choi, Seul Ki, Swann Arp Adams, Jan M. Eberth, Heather M. Brandt, Daniela B. Friedman, Reginald D. Tucker-Seeley, Mei Po Yip, and James R. Hébert. "Medicaid Coverage Expansion and Implications for Cancer Disparities." American Journal of Public Health 105, no. S5 (November 2015): S706– S712. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2015.302876. | ||

* Very early expanding states are those opting to expand Medicaid coverage to childless adults between March 1, 2010 and April 14, 2011.

- Medicaid Is Associated with Identifying Cancer at an Earlier Stage. Identifying cancer at an earlier stage improves survival27, 28 and having Medicaid coverage is linked to earlier detection. For example, a growing body of research analyzing the impact of the ACA expansion on newly diagnosed cancer patients detected a small but significant shift toward early-stage diagnoses. These results have been found for a variety of cancers including for colorectal, lung, breast, pancreatic cancer and melanoma among patients in expansion states.29, 30

The reverse appears to be true as well. Tennessee implemented a policy to substantially limit Medicaid enrollment, and data from this policy showed that losing Medicaid coverage was associated with a higher percentage of women diagnosed with late-stage cancer. In that state, the percentage of women diagnosed with late-stage cancers increased 3.3 percentage points after the policy went into effect.31, 32

- Medicaid is Associated with a Higher Likelihood of Receiving Needed Cancer Treatment and Better Outcomes. Once cancer is detected, costly treatments like surgery, radiation and chemotherapy are often part of the recommended care plan. Compliance with that plan is most likely to result in the best outcomes and in many cases to improve the likelihood of survival. Medicaid coverage removes financial barriers to receiving cancer treatment and increases the likelihood that a person follows through with their cancer care plan. As noted above, cancer survivors in expansion states reported being more able to see a doctor and more likely to have a personal doctor. Medicaid expansion has also been associated with better access to certain cancer treatments. For example, cancer patients in expansion states experience greater use of cancer surgery than those in non-expansion states.33, 34, 35

Even when treatment is sought and a treatment regimen is planned or prescribed, people without insurance coverage fail to comply with those treatment plans at a much higher rate than those with insurance coverage (including Medicaid). For example, as prescription drug costs increase, more individuals are unable to continue to afford their prescription medications. Research examining the ability of cancer survivors to afford their medications indicates that Medicaid coverage has protected individuals from these concerns. Uninsured cancer survivors were increasingly likely to have trouble paying for their prescriptions while cancer survivors with Medicaid did not experience similar challenges.36

- Medicaid Promotes Tobacco Cessation. Because Medicaid programs are required to cover smoking cessation services for the ACA expansion population, increasing access to Medicaid for adults has successfully enabled more people to quit smoking. For example, researchers examining health records for tobacco product users found that the odds of quitting tobacco increased more among individuals in expansion states compared to those in non-expansion states.37 For eligible adults in Medicaid expansion states, the likelihood of quitting smoking was two percentage points higher when compared with smokers in non-expansion states.38 Increasing quit rates can result in improvements to health as well as reduced total health care costs. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated the health improvements from smoking prevention and cessation services would reduce Medicaid costs and enrollees' improved health would result in better earnings and more productivity.39

- Medicaid Provides Individuals & Families Financial Protection. For cancer patients and other individuals diagnosed with a serious medical condition for which expensive treatment is necessary, Medicaid provides individuals and families with financial protection. Medicaid covers the cost of their medical treatment so that they do not have to face financial distress or bankruptcy in order to seek medical care. In addition, Medicaid provides other critical benefits for individuals with cancer or survivors. In most states, Medicaid covers non-emergency medical transportation, which is necessary for people who are too sick to transport themselves to their medical providers or for those who don't have reliable access to transportation. Medicaid also provides retroactive eligibility – covering the costs of medical care incurred during the three months prior to finalizing the eligibility process for individuals who would have been eligible during those months. For individuals newly diagnosed with cancer or whose income is being depleted to cover medical expenses incurred prior to being deemed eligible for Medicaid, retroactive eligibility can make the difference between accessing treatment or dangerously delaying or avoiding treatment altogether.

Medicaid's financial protection is particularly important to people with cancer and survivors because they are often unable to work or are limited in the amount or kind of work they can do because of health problems related to their cancer diagnosis.40, 41, 42 Research indicates that between 40 and 85% of cancer patients stop working while receiving cancer treatment, with absences from work ranging from 45 days to six months depending on the treatment.43 Recent cancer survivors often require frequent follow-up visits and maintenance medications to prevent recurrence, and suffer from multiple comorbidities linked to their cancer treatments.44, 45 These realities make maintaining their professional lives increasingly difficult, as confirmed by research indicating that people with a history of cancer are more likely to lose their jobs and their job-based insurance coverage.46, 47 Cancer survivors who continue working find that they cannot adjust their work schedules, reduce their hours, change or leave their jobs for fear of losing their health insurance.48

- Medicaid Expansion Has a Positive Impact on States' Economies. In addition to the enrollees being positively impacted by Medicaid expansion, states and providers also benefit economically from Medicaid expansion. Following implementation of Medicaid expansion, states found that the increased federal funds available to them lessened the burden of uncompensated care on hospitals,49 reduced the risk of hospital closures,50, 51, 52 increased the number of jobs (in particular jobs in the health care sector), and increased tax revenues for states and localities.53

Contrary to claims that Medicaid expansion is busting state budgets, early peer reviewed analyses concluded that, instead of Medicaid expansion raising costs for states, "there were not significant increases in spending from state funds as a result of the expansion" even though many states enrolled more individuals than projected.54

The cost of expanding coverage in many of those states was offset by savings in a number of other areas – state-funded behavioral health care services,55, 56, 57 reductions in recidivism at state correctional facilities/ county and local jails,58 and state and local programs for the uninsured and charity care for example. States were also able to increase their revenue from provider and insurer taxes.

It is not yet known whether those economic advantages will continue to persist for states as they are now required to fund a larger share of the costs of new ACA eligibles than during the initial years of the expansion, although Medicaid experts predict that those costs are likely to continue to be modest.59

Policies That Impede Access to Medicaid

Certain Medicaid policies under discussion or being implemented in states under federal research and demonstration waivers potentially threaten access to Medicaid for all enrollees. But because of the ongoing need for uninterrupted access to medical care for people with cancer or survivors, such policies are particularly concerning.

Capping Medicaid Spending

A policy discussion that has taken place periodically since the early 1980s involves establishing caps on the federal share of spending for the Medicaid program. Medicaid spending caps have been included in a number of bills offered in Congress and in budget proposals both in Congress and by several administrations. These discussions have failed for many reasons, including concerns that federal spending under the capped program would be insufficient to meet Medicaid enrollees' needs. The complexity of negotiating greater program flexibility for states in exchange for limited federal financing was also a factor.

In 2019, press reports indicate that the Administrator of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has invited states to propose demonstrations that would incorporate federal caps on Medicaid state spending. Forthcoming guidance under review at the OMB is expected to lay out a framework for those demonstrations.60, 61

Two states are moving forward in advance of the CMS waiver guidance allowing states to impose budget caps on program spending. In September 2019, Tennessee released an 1115 block grant waiver proposal, signaling its intent to seek federal approval of a federal funding cap.62 It should be noted that Tennessee has not expanded Medicaid eligibility as provided under the ACA, so if approved, this funding cap would apply to the traditional Medicaid population.

The state of Utah has also submitted an 1115 waiver application that includes a per person (or per capita) cap on the amount of funding that the state would receive from CMS for Medicaid enrollees, depending on their category of eligibility. Although the proposal was denied by CMS in August 2019, the state's plan suggests that it will be modified and re-submitted.63

Implications of Capping Medicaid for Beneficiaries: There are two general approaches for imposing budget ceilings on Medicaid programs. Under a block grant, the state's entire Medicaid program or some portion of it would be subject to a cap on federal contributions. The total cap on federal spending for the program could be set in any number of ways – for example, to achieve a particular level of budgetary savings, or it could be based on spending in a recent historical year and then increased each year to reflect medical price inflation or general price inflation. Under the per capita cap approach, per person spending ceilings would be set so that total Medicaid spending in each state would still expand or contract with increasing or shrinking enrollment. That approach would provide some protection for states and Medicaid enrollees should the economy enter a recession or a disaster strikes leaving many more people vulnerable and in need of Medicaid services.

The Tennessee draft plan includes elements of both a block grant and a per capita cap insofar as if enrollment were to grow in excess of the state's projections, its block grant amounts would also grow to reflect the additional enrollment.

Both of those arrangements are in contrast to federal financing under existing law, where Medicaid spending rises with each state's need and policy choices and is essentially uncapped so long as a state is able to raise its own share of program costs and is only covering medical benefits permitted under federal law.

Whether block grants or per capita caps are considered, both types of ceilings on federal spending undermine the financing guarantee of comprehensive Medicaid coverage. Over time, should states find that the federal funds available are no longer sufficient to cover the cost of covered Medicaid services, states could be forced to either raise additional state funds to pay for services without any additional federal assistance or to make cuts to their programs. Neither block grants nor per capita caps necessarily consider medical inflation or the introduction of new costly specialty drugs or medical treatments. While per capita caps offer some protection in the event of a recession, because funding would rise as the number of people on the program rises, the amount of that protection isn't clear. For example, if the caps rise more slowly than medical costs rise, then state funding may not be able to increase enough to cover enrollment increases or the cost of providing Medicaid benefits to eligible individuals.

Medicaid enrollees, including those with a history of cancer, could be negatively affected in a number of ways. The new flexibilities could make it easier for states to reduce provider payment rates; limit, restrict or eliminate benefits and services; increase cost sharing or freeze/reduce eligibility. The budgetary pressure of a federal spending ceiling could make these alternatives all but necessary. If states reduced payment rates, fewer providers might be willing to accept Medicaid patients, especially since Medicaid's reimbursement rates are already significantly below those of Medicare or private insurance for some of the same services. If states reduced covered services or increased cost sharing, enrollees – including those with cancer – may delay or forgo needed medical care. And if states narrowed their eligibility categories (including Medicaid expansion), some of those enrollees could lose access to Medicaid coverage altogether.

Under these scenarios, Medicaid spending caps could undo the progress made in reducing the number of people without insurance, improving access to timely and appropriate care, and increasing utilization of primary, preventive and diagnostic testing.

States at Financial Risk: Under both types of caps, states that experience unanticipated costs in excess of their caps would no longer be able to share those costs with the federal government. States that have indicated interest in participating in such demonstrations expect that they would be provided with more flexibility and authority to reduce: benefits and services, rates, and/or enrollment. Further, states will likely seek to impose higher out-of-pocket cost sharing on enrollees and more penalties for non-compliance with administrative, wellness and other reporting requirements. While the new flexibilities that states are seeking under these type of 1115 waivers have not been specified in great detail, people with a history of cancer could potentially lose benefits, lose coverage or face increased difficulty accessing the timely and appropriate care they need.

Implications for Providers: If states were to reduce providers' payment rates in response to budget ceilings, more providers would likely decline to participate in the program or stop taking new Medicaid patients. Providers operating in low-income or rural areas who traditionally treat many uninsured and Medicaid enrollees could

be impacted the most. These types of arrangements could contribute to more hospital closures and have a detrimental impact on access for Medicaid enrollees.

Status: In addition to Tennessee and Utah, other states are reported to be interested in participating in a Medicaid budget cap demonstration.64 Without additional information about how restrictive the budget caps would be or the additional flexibility that states would be provided as a trade-off, it is difficult to project the number of states that might seek federal funding cap waivers and the types of proposals they may submit. As an example, while the Tennessee block grant waiver proposal does not appear to be overly restrictive, there is very little detail on the potential impact of higher-than-expected costs to administer the program and the risk for program enrollees, providers and the state. It should also be noted that Tennessee's waiver requests an exemption from all future federal mandates – a flexibility that seems well beyond the waiver authority provided to the Secretary in Section 1115 of the Social Security Act, which authorizes Medicaid research and demonstration waivers.

If approved, it is likely that a legal challenge would arise. Some organizations have expressed, in response to the Secretary's statements, that the Administration does not have the authority to permit such 1115 waivers because Medicaid's financing provisions are not permitted to be waived under that authority.65

Other lawsuits (described below) in response to existing Medicaid demonstration waivers raise the possibility that the courts could halt implementation of these waivers if they conclude that the waivers are designed to restrict access to Medicaid rather than promote the program's objective to make medical assistance available to people who qualify for it.66

Medicaid Demonstration Waivers

Since 2014, a number of states have combined Medicaid expansion with demonstrations authorized under 1115 waivers. Section 1115 permits states to test policies that are not permitted under traditional Medicaid. Under that authority, the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) is able to waive certain federal requirements of the Medicaid program to allow states additional flexibility in designing their programs.

Many of the features of recent demonstrations, however, erect barriers to obtaining or continuing Medicaid coverage (see Table 2 below). Some states have used the demonstration authority to implement provisions that raise premiums or copayments for new ACA expansion enrollees (and sometimes for traditional Medicaid enrollees as well), to restrict benefits, or to put other limits on eligibility or enrollment. Policies that impede, delay, or truncate access to Medicaid can raise major concerns for people with a history of cancer. Concerning policies implemented by some states under these Section 1115 waivers include:

- Imposing Higher Premiums and Copayments: Under usual Medicaid rules, most Medicaid enrollees cannot be charged premiums or enrollment fees that exceed nominal amounts. Seven states have received waivers of those rules so that they can impose premiums, monthly fees, and higher cost sharing amounts for the ACA expansion population (Arkansas, Arizona, Indiana, Michigan, Montana, New Mexico). Two states impose premiums on certain traditional coverage groups, as well (Indiana, Wyoming). Some of those programs include strict consequences of non-payment of premiums or monthly enrollment fees including disenrollment or being locked out of the program for a period of six months. These policies hurt the most vulnerable Medicaid enrollees who are already financially strained. Premiums can prevent low-income people from enrolling in coverage and make it harder to keep Medicaid. Lock-out provisions can cut off access to medical care and for a person in active cancer treatment, this could lead to disruptions in care that could negatively impact their outcome.

Cost sharing and related penalties for non-payment have been shown to create administrative burdens

for enrollees,67 deter enrollment or result in a high number of disenrollment,68 and could potentially cause significant disruptions in care, especially for cancer survivors and those newly diagnosed. Studies have shown that imposing even modest premiums on low-income individuals is likely to deter enrollment in the Medicaid program.69, 70, 71 Imposing copayments on low-income populations has been shown to decrease the likelihood that they will seek health care services, including preventive screenings.72, 73, 74 Cancers that are found at an early stage through screening are less expensive to treat and lead to greater survival.75 Uninsured and underinsured individuals already have lower screening rates resulting in a greater risk of being diagnosed at a later, more advanced stage of disease.76 Proposals that place greater financial burden on low- income residents create barriers to care and could negatively impact Medicaid enrollees – particularly those individuals who are high service utilizers with complex medical conditions.

Copayments can be particularly problematic for people in cancer treatment or survivors. For a person who is seeing multiple providers, being treated with expensive drug therapies or chemotherapy, and undergoing many different types of treatments, even modest copays can add up very quickly. The inability to pay a copayment could also prevent a person from seeking appropriate medical care or following up on recommended treatments, impacting their health outcomes.

-

Eligibility Rules that Restrict Access to Coverage: A number of approved and pending waivers include eligibility provisions that make it harder to qualify for Medicaid through enrollment caps. An enrollment cap would permit the state to stop enrolling new individuals once a certain enrollment level has been reached. South Carolina has applied for approval to impose enrollment caps on chronically homeless, justice-involved and adults with substance use disorders.77 Utah received approval from CMS for an enrollment cap on similar groups and requested to cap enrollment for adults in the expansion population, which CMS denied.

-

Time Limits on Eligibility: South Carolina has a pending application to implement a 12-month time limit on Medicaid coverage for certain populations including childless adults, people who are chronically homeless, and those in need of treatment for mental health or substance use disorders.78 Time limits prevent people from maintaining continuity of coverage and undermine the financial stability of Medicaid enrollees.

Any of these policies could place a substantial financial burden on enrollees and cause significant disruptions in care, especially for individuals battling cancer and recent survivors who require frequent follow-up visits and maintenance medications. These policies could also negatively impact health care providers.

-

Lock-outs: Several states have approval from CMS to lock an expansion enrollee out of the Medicaid program for a period of time for non-payment of premiums (Indiana, Michigan, Montana, and New Mexico). Utah proposed to lock out a beneficiary who engages in an "intentional program violation." Under that proposal, an intentional program violation would include not reporting a change in income or other pertinent change within 10 days or withholding facts when applying to become or remain eligible for Medicaid.

Locking a beneficiary out of Medicaid coverage for a period of time is particularly problematic for cancer patients or survivors who require frequent medical interventions, visits, and maintenance care79 and who suffer from multiple comorbidities linked to their cancer treatments.80 Being denied access to one's cancer care team could be a matter of life or death for a cancer patient or survivor and the financial toll that the lock- out would have on individuals and their families could be devastating.

-

Elimination of Presumptive/Retroactive Eligibility: Five states waive Medicaid's retroactive eligibility requirement under which Medicaid covers medical bills incurred during the three months prior to an individual's Medicaid application if the individual would have been eligible during these months. In most cases, when retroactive eligibility is waived, coverage begins once the application is completed. States waiving retroactive eligibility often combine that waiver with the addition of premiums or enrollment fees, in which case coverage begins once the enrollee has paid their initial premium or enrollment fee. Indiana has

an approval to waive retroactive eligibility for the ACA expansion population; Florida has approval to waive retroactive eligibility for non-expansion adults; and Arizona, Iowa, and New Mexico have approval to waive retroactive eligibility for both groups.81 Others waive presumptive eligibility which means that coverage can only begin after all of the applicant's documentation has been reviewed and eligibility confirmed. By waiving presumptive eligibility, individuals can no longer have coverage begin as soon as the application is submitted. -

Limits on Benefits: One state (Massachusetts) applied for the flexibility to implement a closed formulary for its prescription drug coverage but CMS rejected the application.82 Under existing law, a state is required to cover all of the drugs of a manufacturer for which there is a Medicaid rebate agreement. This requirement limits the ability of states to restrict their drug coverage. The state sought permission to limit its coverage to at least 1 drug per therapeutic class and to create a selective specialty pharmacy network to increase cost effectiveness. A second state is exploring formulary limitations. Tennessee's draft block grant waiver application includes formulary limitations. The state proposes to adopt a "commercial-style closed formulary" that would include at least one drug per therapeutic class. The state claims that this policy would permit it to negotiate more favorable rebate agreements with manufacturers. The state would also exclude new drugs approved through the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) accelerated pathways from its formulary until the state approves of their prices or the state determines that the drug is cost effective.83

There is no single oncology drug that is medically appropriate to treat all cancers. Cancer is not just one disease, but hundreds of diseases. Cancer tumors respond differently depending on the type of cancer, stage of diagnosis, and other factors. Oncology drugs often have different indications, different mechanisms of action, and different side effects – all of which need to be managed to fit the medical needs of an individual. Oncologists take into consideration multiple factors related to expected clinical benefit and risks of oncology therapies and the patient's clinical profile when making treatment decisions. For example,

one fourth of cancer patients have a diagnosis of clinical depression,84 which may be managed with pharmaceutical interventions that may limit cancer treatment options because of drug interactions or side effects. As such, when enrollees are in active cancer treatment, it can be particularly challenging to manage co-morbid conditions.Allowing for the use of a closed formulary would severely restrict a physician's ability to prescribe the medically appropriate treatment for an individual. When enrollees are denied access to medically appropriate therapies, it can result in negative health outcomes, which can increase Medicaid costs in the form of higher physician and/or hospital services to address the negative health outcomes.

Table 2. Selected Provisions of Medicaid Research and Demonstration Waivers, 2019

| Waiver Provision | ACA Expansion Population | Non-Expansion Population | ||||

| Approved | Pending | Set Aside by Court | Approved | Pending | Set Aside by Court | |

| Premiums & Copayments | ||||||

| Require Premiums or Monthly Contribution | AR, AZ, IA, IN, MI, MT, NM | VA | KY | IN, WI | KY | |

| Coverage Loss and Lock-Out for Non- Payment of Premiums | IN, MI, MT, NM | VA | KY | WI | ||

| Disenrollment (w/o Lock-Out) for Non- Payment of Premiums | AZ, IA | |||||

| Tobacco Premium Surcharge | IN | IN | ||||

| Eligibility Rules | ||||||

| Authority to cap enrollment | UT | SC | ||||

| Waive Retroactive Eligibility* | AZ, IA, IN, NM | AR, NH, KY | AZ, FL, IA, NM | KY | ||

| Time Limit on Coverage | SC | |||||

| Eliminate Hospital Presumptive Eligibility | UT | |||||

| Eligibility Determinations and Redeterminations | ||||||

| Lock-out for Failure to Timely Renew Eligibility | IN | KY | KY | |||

| Lock-out for Failure to Timely Report Changes Affecting Eligibility | KY | KY | ||||

| Lock-out for Intentional Program Violations | UT | |||||

Source: KFF analysis of approved and pending waiver applications posted on Medicaid.gov available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid- waiver-tracker-approved-and-pending-section-1115-waivers-by-state/#Table3

Notes: Six other states (DE, MA, MD, RI, TN, and UT) have retroactive coverage waivers that pre-date the ACA some of which apply to limited populations.

Conclusion

Many individuals with low incomes, including those with cancer and cancer survivors, rely on Medicaid for cancer prevention, early detection, and diagnostic and treatment services. Medicaid increases access to doctors, preventive screenings, and cancer treatment as well as treating the conditions that cancer leaves in its wake.

It helps people with cancer be productive at work for as long as possible and helps them to avoid becoming financially devastated by medically necessary lifesaving treatments. For many people, access to health coverage through Medicaid also provides them access to the medications they need to keep their job, stay healthy, and care for their family and loved ones. The Medicaid program helps providers to continue to serve low-income individuals and families and helps local communities and economies thrive. Changes to the Medicaid program should enhance – not restrict – access to the kind of care cancer patients and survivors need most.

1 Analysis provided to ACS CAN by Avalere Health. Coverage of patients with cancer in Medicaid under the AHCA. Analysis performed June 2017.

2 "MACStats: Medicaid and CHIP Data Book," Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, accessed July 2019, https://www.macpac.gov/ wp-content/uploads/2015/01/EXHIBIT-1.-Medicaid-and-CHIP-Enrollment-as-a-Precentage-of-the-U.S.-Population-2017.pdf.

3 "Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights," Medicaid.gov (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services), accessed July 2019, https://www.medicaid. gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html.

4 The Aid to Families with Dependent Children program was replaced in 1996 by the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program.

5 Including establishing the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in 1997. Under CHIP, Congress permitted states to be able to choose to provide modest-income children with Medicaid or with separate coverage under a new program.

6 "Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000," Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000 § (n.d.), https:// www.congress.gov/bill/106th-congress/house-bill/4386.

7 "Medicaid Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program Enrollment," The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, accessed July 2019, https://www.kff.org/ other/state-indicator/medicaid-breast-and-cervical-cancer-treatment-program-enrollment/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Loca- tion%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

8 "NBCCEDP Screening Program Summaries," National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/nbccedp/data/summaries/.

9 The ACA extended coverage for adults with income below 133% of FPL but allowed states to disregard of 5% of income, summing to 138% of FPL.

10 King v. Burwell, 576 U.S. _ (2015).

11 Missouri and Oklahoma are considering 2020 ballot initiatives, that, if successful could authorize an expansion of eligibility of the states' Medicaid program

up to 138% FPL. As of October 2019, the North Carolina legislature was still considering legislation that could authorize an expansion of the state's Medicaid program.

12 Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, "Mandatory & Optional Benefits," Medicaid.gov, accessed July 2019, www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/list- of-benefits/index.html..

13 Samantha Artiga et al., "Current Flexibility in Medicaid: An Overview of Federal Standards and State Options," The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, January 31, 2017, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/current-flexibility-in-medicaid....

14 Analysis provided to ACS CAN by Avalere Health. Coverage of patients with cancer in Medicaid under the AHCA. Analysis performed June 2017.

15 A recent Census Bureau report found that in 2018, for the first time since 2009, the uninsured rate ticked up while Medicaid enrollment declined. See Edward R. Berchick, Jessica C. Barnett, and Rachel D. Upton, "Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2018," United States Census Bureau, November 2019, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2019/demo....

16 Sarah Miller and Laura R. Wherry, "Health and Access to Care during the First 2 Years of the ACA Medicaid Expansions," New England Journal of Medicine 376, no. 10 (March 9, 2017): pp. 947-956, https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa1612890.

17 Sarah Miller and Laura R. Wherry, "Four Years Later: Insurance Coverage and Access to Care Continue to Diverge between ACA Medicaid Expansion and Non-Expansion States," American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings 109 (May 2019): pp. 327-333, https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20191046.

18 For a comprehensive literature review of Medicaid expansion related research, see Larisa Antonisse et al., "The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review," The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, August 15, 2019, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the- effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-august-2019/.

19 Xuesong Han et al., "Comparison of Insurance Status and Diagnosis Stage Among Patients With Newly Diagnosed Cancer Before vs After

Implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act," JAMA Oncology 4, no. 12 (December 2018): pp. 1713-1720, https://doi.org/10.1001/ jamaoncol.2018.3467.

20 Amy J. Davidoff et al., "Changes in Health Insurance Coverage Associated With the Affordable Care Act Among Adults With and Without a Cancer History," Medical Care 56, no. 3 (March 2018): pp. 220-227, https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000876.

21 Robin Rudowitz, Rachel Garfield, and Elizabeth Hinton, "10 Things to Know about Medicaid: Setting the Facts Straight," The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, March 6, 2019, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/10-things-to-know-about-medicai....

22 "Key Findings on Access to Care" Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/measuring-and-monitoring- access/.

23 Wafa W. Tarazi et al., "Medicaid Expansion and Access to Care among Cancer Survivors: a Baseline Overview," Journal of Cancer Survivorship 10, no. 3 (June 2016): pp. 583-592, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0504-5.

24 Jack Hadley, "Sicker and Poorer—The Consequences of Being Uninsured: A Review of the Research on the Relationship between Health Insurance, Medical Care Use, Health, Work, and Income," Medical Care Research and Review 60, no. 2_suppl (June 2003): p. 3S-75S; discussion 76S-112S, https:// doi.org/10.1177/1077558703254101.

25 "Key Facts about the Uninsured Population," The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, December 7, 2018, http://files.kff.org/attachment//fact-sheet-key- facts-about-the-uninsured-population.

26 Jack Hadley, "Sicker and Poorer—The Consequences of Being Uninsured: A Review of the Research on the Relationship between Health Insurance, Medical Care Use, Health, Work, and Income," Medical Care Research and Review 60, no. 2_suppl (June 2003): p. 3S-75S; discussion 76S-112S, https:// doi.org/10.1177/1077558703254101.

27 Elizabeth Ward et al., "Association of Insurance with Cancer Care Utilization and Outcomes," CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 58, no. 1 (2008): pp. 9-31, https://doi.org/10.3322/ca.2007.0011.

28 Michael T. Halpern et al., "Association of Insurance Status and Ethnicity with Cancer Stage at Diagnosis for 12 Cancer Sites: a Retrospective Analysis," The Lancet Oncology 9, no. 3 (March 2008): pp. 222-231, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(08)70032-9.

29 Ahmedin Jemal et al., "Changes in Insurance Coverage and Stage at Diagnosis Among Nonelderly Patients With Cancer After the Affordable Care Act," Journal of Clinical Oncology 35, no. 35 (December 10, 2017): pp. 3906-3915, https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2017.73.7817.

30 Aparna Soni et al., "Effect of Medicaid Expansions of 2014 on Overall and Early-Stage Cancer Diagnoses," American Journal of Public Health 108, no. 2 (February 1, 2018): pp. 216-218, https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2017.304166.

31 Wafa W. Tarazi et al., "Impact of Medicaid Disenrollment in Tennessee on Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis and Treatment," Cancer 123, no. 17 (September 1, 2017): pp. 3312-3319, https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30771.

32 Xuesong Han et al., "Comparison of Insurance Status and Diagnosis Stage Among Patients With Newly Diagnosed Cancer Before vs After Implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act," JAMA Oncology 4, no. 12 (December 2018): pp. 1713-1720, https://doi.org/10.1001/ jamaoncol.2018.3467.

33 Wafa W. Tarazi et al., "Impact of Medicaid Disenrollment in Tennessee on Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis and Treatment," Cancer 123, no. 17 (September 1, 2017): pp. 3312-3319, https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30771.

34 Andrew B. Crocker et al., "Expansion Coverage and Preferential Utilization of Cancer Surgery among Racial and Ethnic Minorities and Low-Income Groups," Surgery 166, no. 3 (September 2019): pp. 386-391, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2019.04.018.

35 Emanuel Eguia et al., "Impact of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid Expansion on Cancer Admissions and Surgeries," Annals of Surgery 268, no. 4 (October 2018): pp. 584-590, https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000002952.

36 Min Jee Lee, M. Mahmud Khan, and Ramzi G. Salloum, "Recent Trends in Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence Among Cancer Survivors in the United States," Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy 24, no. 1 (January 2018): pp. 56-64, https://www.jmcp.org/doi/pdf/10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.1.56.

37 Steffani R Bailey et al., "Tobacco Cessation in Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion States Versus Non-Expansion States," Nicotine & Tobacco Research, May 23, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntz087.

38 Jonathan W. Koma et al., "Medicaid Coverage Expansions and Cigarette Smoking Cessation Among Low-Income Adults," Medical Care 55, no. 12 (December 2017): pp. 1023-1029, https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000821.

39 Congressional Budget Office, "Raising the Excise Tax on Cigarettes: Effects on Health and the Federal Budget," (Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office, 2012). http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/06-13-Smokin....

40 Gery P. Guy et al., "Annual Economic Burden of Productivity Losses Among Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancers," Pediatrics 138, no. Supplement 1 (November 2016): pp. S15-S21, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4268d.

41 Zhiyuan Zheng et al., "Annual Medical Expenditure and Productivity Loss Among Colorectal, Female Breast, and Prostate Cancer Survivors in the United States," Journal of the National Cancer Institute 108, no. 5 (December 24, 2015), https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv382.

42 Erin E. Kent et al., "Impact of Sociodemographic Characteristics on Underemployment in a Longitudinal, Nationally Representative Study of Cancer Survivors: Evidence for the Importance of Gender and Marital Status," Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 36, no. 3 (April 10, 2018): pp. 287-303, https://doi. org/10.1080/07347332.2018.1440274.

43 Scott Ramsey et al., "Washington State Cancer Patients Found To Be At Greater Risk For Bankruptcy Than People Without A Cancer Diagnosis," Health Affairs 32, no. 6 (June 2013): pp. 1143-1152, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263.

44 Laxmi S. Mehta et al., "Cardiovascular Disease and Breast Cancer: Where These Entities Intersect: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association," Circulation 137, no. 8 (February 1, 2018): pp. e30-366, https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000556.

45 Emily Dowling et al., "Burden of Illness in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancers," Cancer 116, no. 15 (August 1, 2010): pp. 3712-3721, https://doi. org/10.1002/cncr.25141.

46 Kate Sheridan, "Poor Women More Likely to Lose Their Jobs during Cancer Treatment," STAT News, February 6, 2017, https://www.statnews. com/2017/02/06/poor-women-lose-jobs-cancer/.

47 Larisa Antonisse et al., "The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review," The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, August 15, 2019, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansi... review-august-2019/.

48 Kaan Tunceli et al., "Cancer Survivorship, Health Insurance, and Employment Transitions among Older Workers," INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing 46, no. 1 (March 1, 2009): pp. 17-32, https://doi.org/10.5034/inquiryjrnl_46.01.17.

49 David Dranove, Craig Garthwaite, and Christopher Ody, "The Impact of the ACA's Medicaid Expansion on Hospitals' Uncompensated Care Burden and the Potential Effects of Repeal," The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_... issue_brief_2017_may_dranove_aca_medicaid_expansion_hospital_uncomp_care_ib.pdf.

50 "Vulnerability to Value: Rural Relevance under Healthcare Reform," (iVantage Health Analytics, 2015). http://cdn2.hubspot.net/ hubfs/333498/2015_Rural_Relevance_Study_iVantage_04_29_15_FNL.pdf?__hssc=31316192.5.1430489190714&__hstc=31316192. d0dce9fb5dcfbb09eef9f204e5d14c27.1429107453775.14.

51 Deborah Bachrach et al., "States Expanding Medicaid See Significant Budget Savings and Revenue Gains," ed. Manatt Health, (State Health Reform Assistance Network, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, March 1, 2016), https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2015/04/states-expanding-medica... significant-budget-savings-and-rev.html.

52 Richard C. Lindrooth et al., "Understanding The Relationship Between Medicaid Expansions And Hospital Closures," Health Affairs 37, no. 1 (January 2018): pp. 111-120, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0976.

53 Stan Dorn et al., "The Effects of the Medicaid Expansion on State Budgets: An Early Look in Select States," The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, March 11, 2015, http://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-the-effects-of-the-medicaid-....

54 Benjamin D. Sommers and Jonathan Gruber, "Federal Funding Insulated State Budgets From Increased Spending Related To Medicaid Expansion," Health Affairs 36, no. 5 (May 2017): pp. 938-944, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1666.

55 United States Government Accountability Office (GAO), "Medicaid Expansion: Behavioral Health Treatment Use in Selected States in 2014" (Washington, DC: GAO Report to Congressional Requesters, June 2017), https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/685415.pdf.

56 Samantha Artiga et al., "The Role of Medicaid and the Impact of the Medicaid Expansion for Veterans Experiencing Homelessness," The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2017, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-role-of-medicaid-and-impact... encing-homelessness/.

57 Johanna Maclean and Brendan Saloner, "The Effect of Public Insurance Expansions on Substance Use Disorder Treatment: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act,"(National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 23342, April 2017), http://www.nber.org/papers/w23342.pdf.

58 Jacob Vogler, "Access to Health Care and Criminal Behavior: Short-Run Evidence from the ACA Medicaid Expansions," SSRN Electronic Journal, November 14, 2017, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3042267.

59 Mark Hall, "Do States Regret Expanding Medicaid?," USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy (Brookings, March 30, 2018), https://www. brookings.edu/blog/usc-brookings-schaeffer-on-health-policy/2018/03/26/do-states-regret-expanding-medicaid/.

60 Sandhya Raman, "CMS Leader Outlines Future of Medicaid Flexibility," CQ News, May 31, 2019, https://plus.cq.com/doc/news- 5555346?0&searchId=xvh5tMPq.

61 Judith Solomon and Jessica Schubel, "'Block Grant' Guidance Will Likely Invite Medicaid Waivers That Pose Serious Risks to Beneficiaries, Providers, and States," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 27, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/block-grant-guidance-will-likely-in... ers-that-pose-serious-risks-to.

62 See https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents2/Amendment42Compreh....

63 See https://medicaid.utah.gov/Documents/pdfs/Adult%20Expansion%20Comparison%....

64 Judith Solomon and Jessica Schubel, "'Block Grant' Guidance Will Likely Invite Medicaid Waivers That Pose Serious Risks to Beneficiaries, Providers, and States," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 27, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/block-grant-guidance-will-likely-in... ers-that-pose-serious-risks-to.

65 July 18, 2019 Letter to Seema Verma, Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, https://www.lung.org/assets/documents/advocacy- archive/health-partner-letter-to-cms-1.pdf.

66 Sara Rosenbaum and Alexander Somodevilla, "The Medicaid Work Experiments And The Courts: Round Two," The Medicaid Work Experiments And The Courts: Round Two (Health Affairs Blog, March 19, 2019), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190319.563156/full/.

67 The Lewin Group. "Health Indiana Plan 2.0: POWER Account Contribution Assessment," March 31, 2017, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid- CHIP-Program-Information/ByTopics/Waivers/1115/downloads/in/Healthy-Indiana-Plan-2/in-healthy-indiana-plan-support-20-POWER-acctcont- assesmnt-03312017.pdf.

68 Samantha Artiga, Petry Ubri, and Julia Zur, "The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings," The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, June 1, 2017, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-premiums-and-cos... income-populationsupdated-review-of-research-findings/.

69 Michael Hendryx et al., "Effects of a Cost-Sharing Policy on Disenrollment from a State Health Insurance Program," Social Work in Public Health 27, no. 7 (November 12, 2012): pp. 671-686, https://doi.org/10.1080/19371910903269653.

70 Bill J. Wright et al., "Raising Premiums And Other Costs For Oregon Health Plan Enrollees Drove Many To Drop Out," Health Affairs 29, no. 12 (December 2010): pp. 2311-2316, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0211.

71 "Financial Condition and Health Care Burdens of People in Deep Poverty," Office for the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, July 16, 2015), https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/financial-condition-and-health-care-bu....

72 Geetesh Solanki, Helen Halpin Schauffler, and Leonard S. Miller, "The Direct and Indirect Effects of Cost-Sharing on the Use of Preventive Services," Health Services Research 34, no. 6 (February 2000), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1089084/.

73 James Frank Wharam et al., "Two-Year Trends in Colorectal Cancer Screening After Switch to a High-Deductible Health Plan," Medical Care 49, no. 9 (September 2011): pp. 865-871, https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0b013e31821b35d8.

74 Amal N. Trivedi, William Rakowski, and John Z. Ayanian, "Effect of Cost Sharing on Screening Mammography in Medicare Health Plans," New England Journal of Medicine 358, no. 4 (January 24, 2008): pp. 375-383, https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa070929.

75 American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2019-2020. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2019. 76 Ibid.

77 South Carolina's pending "Community Engagement Section 1115 Demonstration Waiver Application." https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program- Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/sc/sc-community-engagement-pa.pdf.

78 Ibid.

79 National Cancer Institute. Coping with cancer: Survivorship, follow-up medical care. Accessed July 2019. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/ survivorship/follow-up-care.

80 Mehta LS, Watson KE, Barac A, Beckie TM, Bittner V, Cruz-Flores S, et al. Cardiovascular disease and breast cancer: Where these entities intersect: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018; 137(7).

81 Arkansas, New Hampshire, and Kentucky also had waivers approved that would have waived retroactive eligibility but those waivers have been set aside in lawsuits.

82 See https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Wai... amndmnt-appvl-jun-2018.pdf.

83 See https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents2/TennCareAmendment4....

84 American Cancer Society, Coping with Cancer: Anxiety, Fear, and Depression. Available at https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/

emotional-side-effects/anxiety-feardepression.html.

Is Chemotherapy Ever Covered Under Federal Emergency Services

Source: https://www.fightcancer.org/policy-resources/medicaid-ensuring-access-affordable-health-care-coverage-lower-income-cancer

Posted by: dawepith1958.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Is Chemotherapy Ever Covered Under Federal Emergency Services"

Post a Comment